When you see the word “tiny house,” what comes to mind? “Minimalism?” Maybe “decluttering” or “downsizing?” You probably don’t immediately connect “resistance” with the living-small movement that’s cut from the same cloth as Kondo-ing. But for a group of indigenous peoples in Canada, tiny homes are exactly how they plan to protect their ancestral land from big oil.

Since Canadian prime minister Justin Trudeau first committed to expand the Trans Mountain pipeline hundreds of miles from Alberta to the Pacific Coast three years ago, the project has been contested by environmentalists and deemed “shameful” by 16-year-old Greta Thunberg on Twitter. It’s also been denounced by indigenous communities who feel it threatens their sovereignty and their sacrality. To halt construction, activists calling themselves Tiny House Warriors are strategically placing eco-friendly “resistance-homes-on-wheels,” as they describe them, along the pathway of the proposed pipeline.

The mostly female coalition sees potential in tiny houses as symbolic tools for a revolution to retain what’s rightfully theirs. “This isn’t picketing and marching through the streets,” says Tiny House Warrior leader Kanahus Manuel, a Secwepemc land defender. “We are asserting our inherent, God-given right to our lands. We’re defending what’s ours, and tiny homes are how we’re doing it.”

Fans of the micro-living movement hail Henry David Thoreau as the original tiny house evangelist for his two year stint in a 150-square-foot cabin in 1854. When HGTV brought it to the mainstream with Tiny House Hunters over 150 years later, sales in trailer homes, shipping containers, and yurts saw an immediate uptick. Today, 10,000 people in North America live in their own simplistic utopias, seduced by perks like environmental mindfulness. Just search #tinyhouse on Instagram, and you’ll find over one million VSCO-filtered snaps enticing you, too, to take the tiny plunge.

Defined by Curbed as structures under 500 square feet, tiny houses remain enigmatic to many—while others claim they can rejuvenate small towns, shelter the homeless (though they’ve been accused of poverty appropriation), and address the affordable housing crisis.

Manuel first saw them as conduits for social justice during the 2016 resistance efforts against the Dakota Access pipeline at Standing Rock. A group of indigenous women built a small structure on wheels in just one week for her and her four children to reside in while participating in the movement. Its size reminded Manuel of her tribe’s traditional underground pit houses and cedar lodges. Tiny homes, she realized, were the perfect tool to thwart the pipeline threatening to desecrate her own sacred lands.

Back home, Manuel and her sister, Alaina John, formed the Tiny House Warriors and put out calls for volunteer builders and donations, which quickly flooded in from all over the world. Leonardo DiCaprio shared a post about their movement on social media. Jane Fonda sent them money to buy solar panels. Within two weeks, they had more than enough supplies to craft two tiny homes.

Since then, they’ve built four more, with another four in the works. Each has an indoor composting toilet and a wood-burning stove. They’re eco-friendly, solar-powered and completely fossil fuel-free, decorated with intricate murals on the outside depicting indigenous culture. One painting tells the story of how rainbows were created from water splashing off a coyote’s back. Another involves an ancient tale about an elk chief and a swan.

The idea is for Tiny House Warriors to eventually reside in the homes, which they’ll strategically place along a 321 mile stretch of the pipeline’s proposed path. Manuel says the land was never ceded to Canada and cuts through many sacred sites and fasting grounds. Trudea has said profits reaped from the pipeline will be funneled back into green projects and that regulators are consulting with First Nations communities.

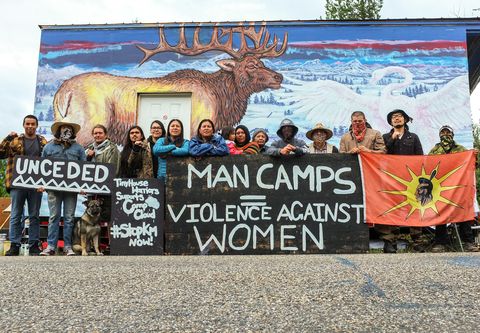

For now, the houses have been wheeled to the border of a temporary community for Trans Mountain pipeline builders. These so-called oil industry “man camps” lead to well-documented increases of violence against indigenous women.

Manuel fears communities near the proposed expansion are at risk. Blockading the camp’s frontlines with their homes, she says, is a way to assert jurisdiction over the land and to assure local women remain safe. “If we let this pipeline construction continue, we just know that it’s going to continue to spiral out of control,” she says.

Women have been leading the fight against controversial pipelines since Standing Rock, where a crop of new activists, many of them indigenous women, rallied to rebel against oil industry titans. The environmental and social justice organizations that subsequently sprung up are also predominately female-led.

Manuel herself comes from a long line of change-makers. Her grandfather, Grand Chief George Manuel, helped enshrine aboriginal rights in the Canadian Constitution and her late father Arthur Manuel, also a former Secwepemc chief, was once described as the “Nelson Mandela of Indigenous Peoples” for his indigenous activism. Her family’s history working on the front lines of land-use rights and resource management inspired Manuel to take action against the Trans Mountain pipeline, which she calls “an ugly symbol of the ongoing legacy of colonialism in North America.”

Though the Tiny House Warriors ultimately want to stop expansion altogether, they offer something more tangible in the process: efficient housing that can revitalize traditional nomadic culture. At a time when 80 percent of indigenous “reserves” in Canada (what we’d call “reservations” in the U.S.) have median incomes below the country’s poverty line, Manuel says their tiny homes—both cheap and easy to build—can help solve a crisis that’s only getting worse.

“This isn’t some trend or fad for us,” Manuel says. “Tiny houses have potential to be so much more than that. We’re here for the long run to fight for our lands.”